Tales of the Unexpected – Part 1

Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

Peter Browning came to Abingdon to run the Austin-Healey Club and ended up as BMC Competitions Manager. Along the way he recalls some interesting and amusing experiences.

In the 1960s I was an active member of my local Harrow Car Club, organising all sorts of events, and it was at a Brands Hatch sprint that I met up with Wilson McComb, then editor of Safety Fast! He invited me to visit MG where I was to find out that this was more than a social factory visit.

Upon arrival I was ushered straight into the hallowed offices of John Thornley, who told me that he was looking for someone to set up a worldwide Austin-Healey Club alongside the MG Car Club, and would I be interested in the job. Obviously I jumped at the invitation, not appreciating that in a very short time this was to lead to an even more exciting career opportunity.

John was passionate about the value of the car clubs, believing that every loyal and active member should be a salesman for the marque and, of course, an on-going potential customer. He saw the clubs as a flagship for the marque, encouraging owners to take pride in their cars and their driving, while well organised club events and particularly motor sport were the best advertisement for Abingdon’s sports cars.

A brief word about how the clubs were run at this time – very different from today. The salaried General Secretary was supported only by a membership secretary who handled all the subscriptions and the ordering of club stationery and club kit. MGCC was a lot bigger than it is today while the new Austin-Healey Club soon added some 10,000 new members to the system. This of course was before the era of computers and word processing, so membership details were recorded on hand written cards while all correspondence and membership notices to members had to be individually typed. Subscriptions were recorded in hand written ledgers. In those days the Centres received a capitation fee for each member which enabled Centres to maintain a reasonable bank balance as well as giving them an incentive to actively seek new members.

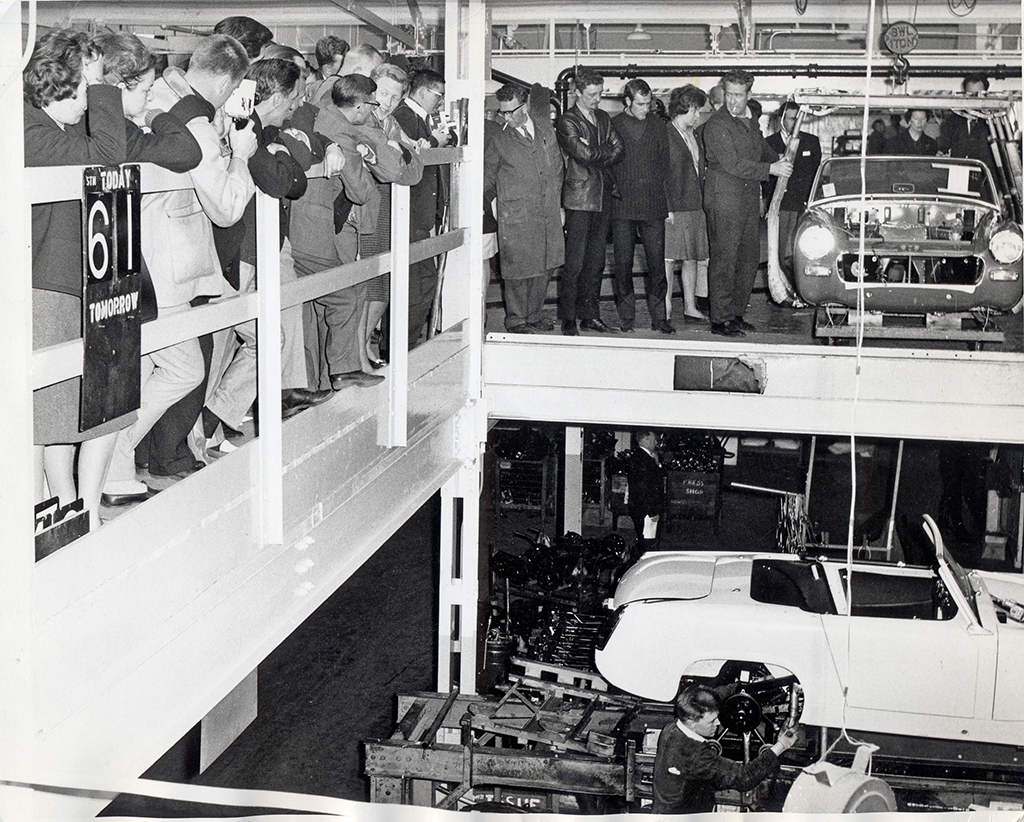

Club visits to Abingdon were always popular, with John Thornley himself usually conducting the factory tour.

My Austin-Healey Club office overlooked the BMC Competitions Department and I had a tantalizing view of the comings and goings of the legendary red and white Minis, MGs and big Healeys. Lunch hours were often spent in Comps seeing the cars being built and chatting to the mechanics.

Before coming to Abingdon I had been an international race timekeeper and was lucky to have had the opportunity to work for some Grand Prix teams across Europe and with sports car entries at Le Mans. Here I was to learn a lot about pit management.

It was through my timekeeping experience that Stuart Turner, then Comps Manager and much involved with the world beating Mini rally programme, asked me to do the timekeeping for the works entered MG and Austin-Healey race sorties. This was to be a unique experience when I got to know the team drivers, mechanics and supporting trade personnel.

The three lone MGB Le Mans entries (1963/5) were early trips and memorable experiences and were a good example of the co-operation that existed between Comps and the Development Department. One of the major challenges for the MGB at Le Mans was qualifying and a significant Le Mans regulation at the time was the minimum practice qualifying time. Thus the specification of the MGB was set very carefully to achieve this by the minimum margin, at the same time adopting a state of tune that would, hopefully, last the 24 hours. We reckoned that the MGB could be struggling to qualify so we asked MG Chief Designer, Syd Enever, to find us more top speed with some improved aerodynamics. Syd came up with the now familiar droop-snout nose (no doubt drawn and calculated in his usual style on the back of a fag packet!). His calculations that the car should reach 140mph were, of course, spot on and the MGB actually clocked 139mph on the Mulsanne Straight and helped us qualify, albeit with a lap time of just 10 seconds in hand.

The MGBs were probably the last true production sports cars to run at Le Mans and in the history of the event I doubt whether any ‘lone’ entry ever achieved the hat trick of finishes. In the three races to have unscheduled pit stops for a slow puncture, a loose exhaust pipe and a broken tail lamp bulb was a fine demonstration of MGB reliability – which was what MGB racing was all about.

I recall one amusing incident at Le Mans with the works Sprite when the inevitable boredom amongst the mechanics led to some high jinks. The French made a big song and dance about the Index of Performance Award, mainly because it was always won by one of the little lightweight French Alpines or Rene Bonnets. The Index Award was based on distance covered and fuel used and with their ultra light weight, streamlined bodies and small engines they always scooped the valued prize.

This year the bored mechanics decided in the early hours of the morning that it was time that the Sprite had a chance to challenge the French. Each pit had its own central refuelling system with its own fuel meter which was read every hour by the officials who then calculated the results. The mechanics broke the seal on the meter, ‘clocked’ the readings to show a reduction in the amount of fuel used and re-sealed the unit. After the next hourly reading there was pandemonium when the Index results were published showing that the Sprite was leading with a fuel consumption of somewhere over 100mpg! Everyone blamed a faulty metering unit, the Sprite had to be deleted from the Index classification (which did not worry anyone) but it all helped to pass the night and annoy the French which was the objective!

With some 80 per cent of Abingdon’s sports car production being exported to the USA, the annual 12 Hour World Championship Sports Car race held at Sebring, Florida was an important annual event for the BMC team. Mind you the track was not really up to European standards for a World Championship event and has been described as Snetterton in the Sahara! It was however one of the most popular sorties for the drivers and mechanics, many of whom had not been to the States before, and we were to enjoy tremendous support and hospitality from the US importers and dealers. The Florida sunshine in March was also particularly welcome after the usual British winter.

My first visit to Sebring was when I went as timekeeper for the team in 1965 and when our connecting flight from New York arrived in West Palm Beach in the early hours of the morning, I somehow got lumbered with sorting out the hire cars; and when I rejoined everyone in the car park I found that they had all taken their seats, leaving me to do the driving. My complaints that I had never been to the States before, never driven left hand drive, and never driven an enormous Cadillac, fell on jet lagged deaf ears and I reluctantly had to set off not having a clue where we were going. Somehow I found my way out of town on the right road in the early hours and settled down to a steady cruising speed on the long straight highways. At every junction I asked for advice but the usual response was either complete silence or a grunt as everyone in the car was asleep.

We had gone about two hours when, bowling along in the pitch dark, suddenly a great black shape shot out from the undergrowth and I hit it fair and square with an alarming thud. It was a big cow which galloped off into the darkness seemingly unhurt, which was more than could be said for our Cadillac which had a crumpled front, some lights missing but luckily no further damage. The only good thing about the incident was that it woke up my passengers with a nasty jolt and when they all got out to survey the damage I quickly jumped into the back seat and forced someone else to take over the driving!

Visiting drivers to Sebring inevitably failed to appreciate the rigid local speed limits and Timo Makinen was one who was pulled up one evening on his way back from the track. Passenger John Rhodes recalls that the police stopped him not only for speeding but clearly just about every other traffic violation in the book. The cops had their guns out of their holsters and looked decidedly serious. Timo, of course, used the old trick of speaking only Finnish and it was left to John to explain that he was the greatest rally driver of all time – and that this was how he always drove. Timo got away with it!

I think that we rewarded the local dealers with a good show at Sebring, and every year from 1964 to 1968, at least one MG outclassed and outpaced the Triumph, Sunbeam, Lotus and Jaguar opposition to be the highest placed British finisher.

Our sorties to the Targa Florio in the 1960s were probably more to do with having the chance to compete in one of the world’s oldest motor races and visit a fabulous island than any other justified reason.

The circuit is really just a long 45 mile rally stage over the twisting narrow mountain roads linked by a four mile flat out straight along the coast road – which leads to some interesting choice of final drives. A feature of the event is the experience of the cars passing through the villages with little old ladies sitting on the pavement doing their knitting and only moving their feet when a works Ferrari in full flight drifts just a little too close to the kerb.

Apart from the local drivers and the annual Targa specialists, few drivers claim to be able to remember the whole circuit and many rely on their own pace note signs painted on the scenery. Naturally the night before the start the locals, and possibly some of the drivers, go out and paint over the signs or add their own versions just to confuse.

The Sicilians do not exactly help when on the eve of the race, the road menders decide that this is the time to try and repair the ravages of the week’s frantic practice when the already poor road surface produces more pot holes and sections of tarmac in serious need of repair. Thus the donkey carts set off from the villages laden with sand, gravel and some poor substitute for road dressing and proceed to create many new hazards.

During the week before the start everyone practises in hire cars and the local hire companies import ship loads of already clapped out cars from the mainland, most of which are totally wrecked by the end of race week or end their life in a Sicilian ditch.

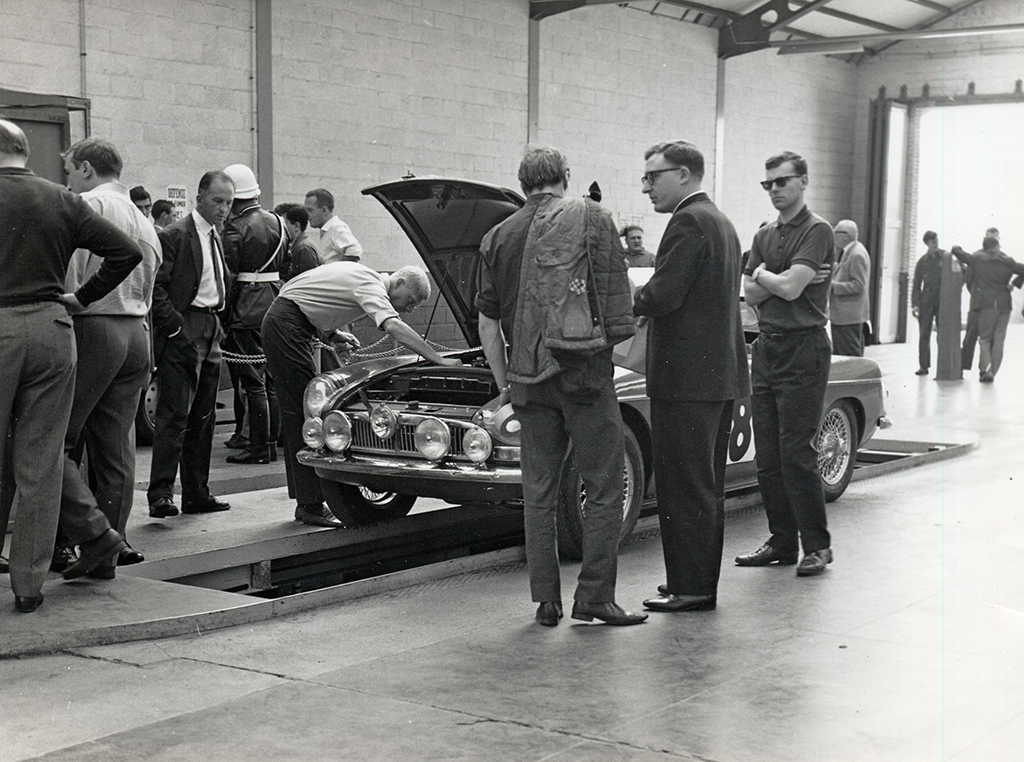

In the 1966 race I remember there were dramas at scrutineering when the works Sprite was found to be considerably underweight, which prompted the ever resourceful Geoff Healey to ask for the car to be weighed again. This time he stood with one foot on the weighbridge to bring it up to the right figure! Then for some reason one of the MGBs had been sent with no bumpers and this contravened the local regulations. Where to find MGB bumpers in a Sicilian village on a Saturday morning – look in the car park and find an English spectator’s car and pinch his! Needless to say the owner was later invited to Abingdon, given a VIP tour of the factory and a new set of bumpers.

This year the John Rhodes MGB started to use a serious amount of oil and John realised that the car was never going to make it back to the pits and he was going to have to try to find a garage somewhere in one of the villages and get some oil. John could not remember the Italian world for oil but fortunately when he came to a village with a garage there was a large Fina advert for oil and he was able to get the spectating mechanics to top up the car. He reckons that he must be the only driver in a World Championship Sports Car Race to have stopped at a garage for service!

John Rhodes drove the MGB like a Mini on the 1966 Targa Florio hoping to find somewhere along the way to top up with oil!

How our MGB won the 84 Hour Marathon in 1966 at the Nurburgring has been told many time and the full story filled many pages in Safety Fast! at the time. Ending up in a ditch on the first lap was not exactly planned but made the drive by Andrew Hedges and Julien Vernaeve through the field to beat the considerable opposition even more creditable. Again reliability won the day over the 5,600 miles ‘race’.

Andrew Hedges (left) and Julien Vernaeve, winners of the 84 Hour Marathon at the Nurburgring – the world’s longest motor race.

It was just before Christmas 1966 that John Thornley called me unexpectedly into his office. He sat me down, paced up and down the room in his usual manner in front of the stone fireplace beneath the classic oil painting of MGs racing at Brooklands. He poured the traditional glass of sherry and I knew that I had either got the sack or that something serious was in the air!

“Got a new job for you,” he said. “Stuart Turner is leaving us and you’re going to be the new Competitions Manager.” That was the only time that I ever had any disagreement with John Thornley. I protested that I really did not think that I could do the job but, of course, I lost the argument.

The next few years were to add a few more ‘Tales of the Unexpected’ which will be told in Part 2.

MG Car Club

MG Car Club