Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

Bonneville Swan Song

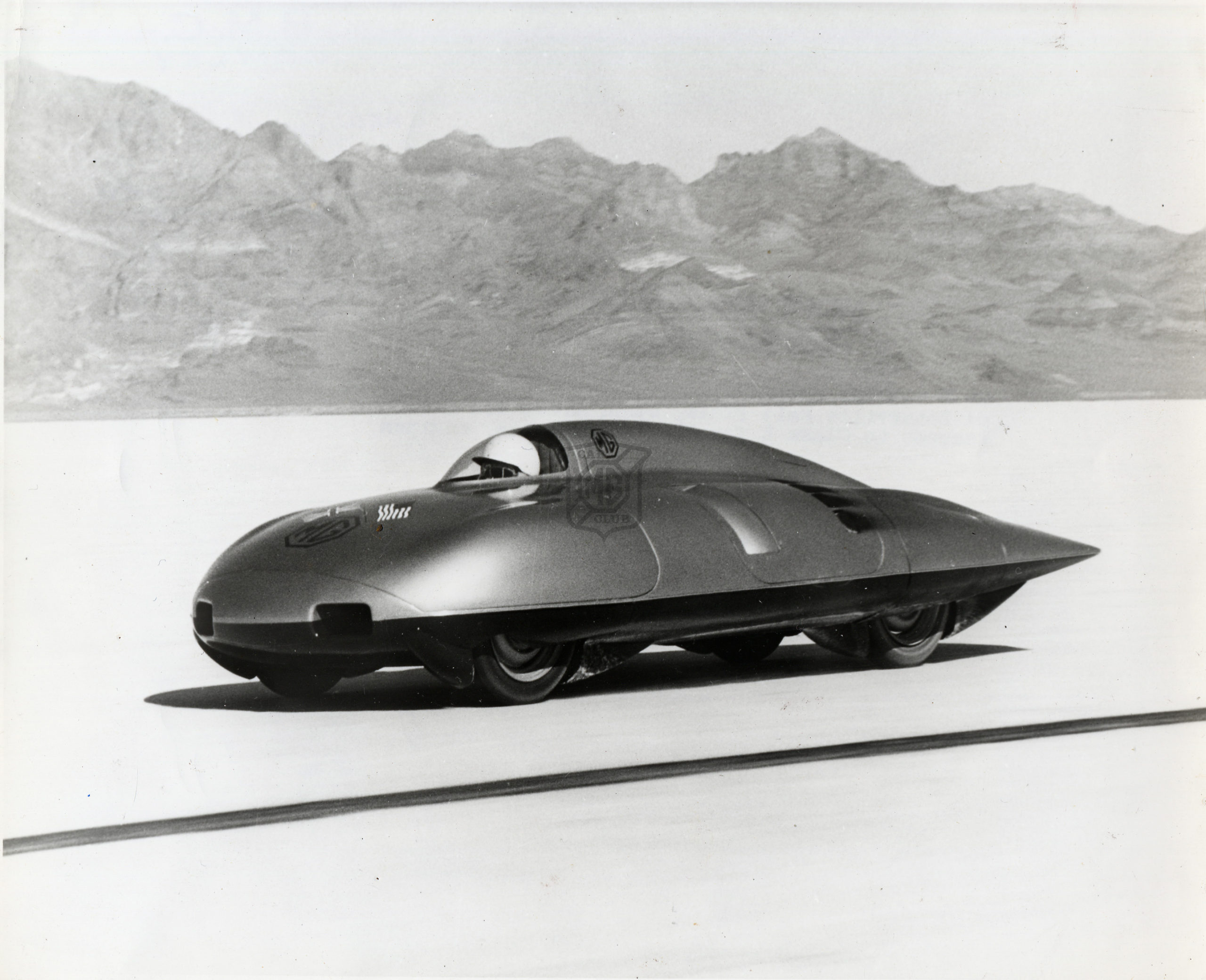

Anniversaries are coming thick and fast at the moment but one that shouldn’t be allowed to slip by without a mention is that almost half a century has passed by since Abingdon last went record breaking. It is fifty years ago this October that EX181 was wheeled out onto the Bonneville salt flats in the state of Utah in the USA to attack existing international records in both class E (1501 to2000cc) and Class F (1101 to 1500cc) over distances from 1 km. to 10 miles. EX181 had already shown its mettle in 1957 when, with its blown 1489cc engine, it achieved a speed of 245.64mph over the measured kilometre in the hands of Stirling Moss.

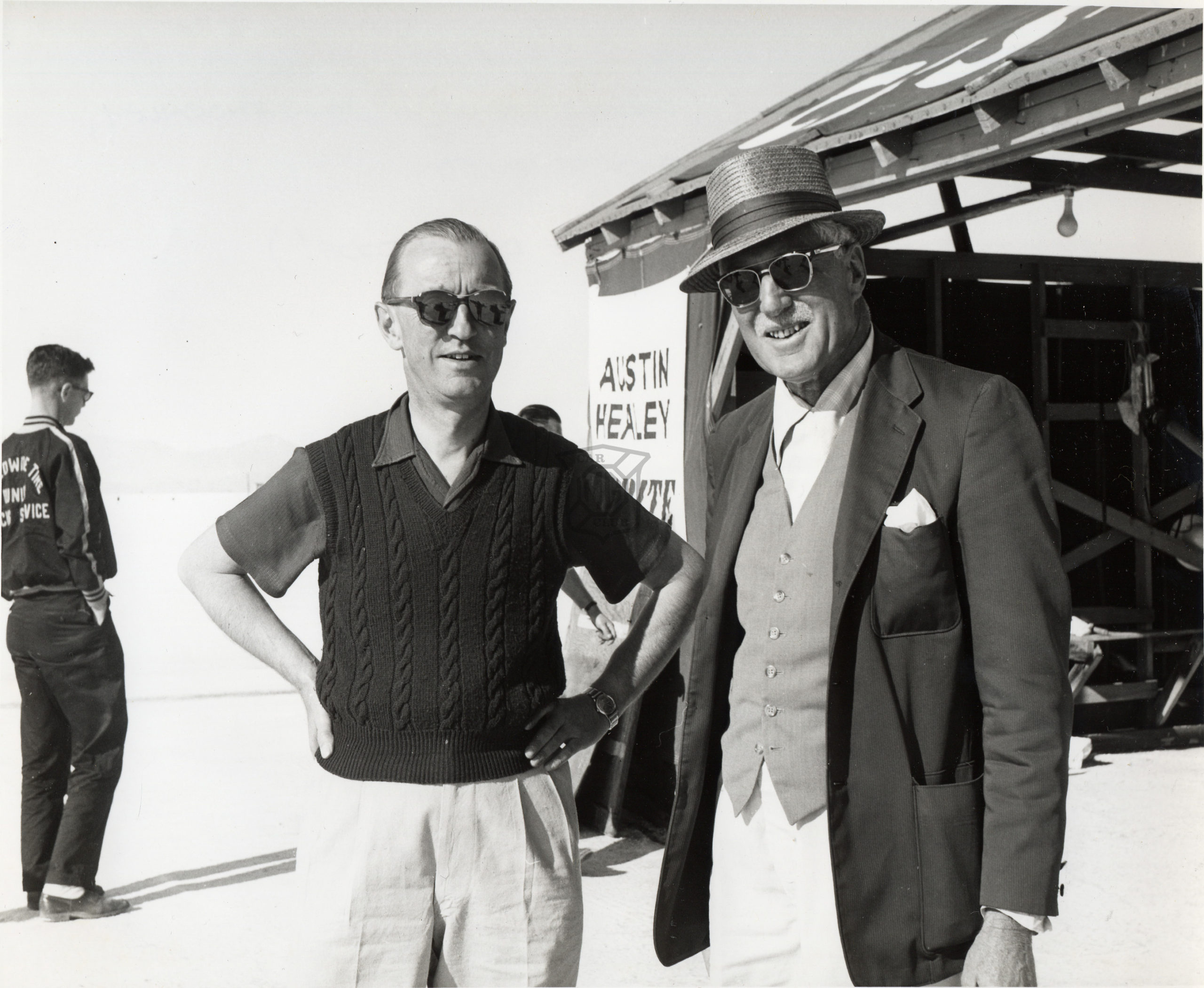

Work on the design of EX181 began as early as 1954 (which is why it is one number lower than the 1955 Le Mans cars) and was the brainchild of George Eyston, who probably broke more speed records in his lifetime than any man before or since. As a director of Castrol Ltd. he was also in the position of offering a certain amount of funding for the project, which probably enabled him to persuade the chairman of BMC, Sir Len Lord, to approve the building of a suitable car by MG for the purpose. It was Castrol too who suggested the (at that time seemingly outrageous) target of 250mph.

At this point the project was handed over to Abingdon’s chief engineer, Syd Enever. Syd sketched out what he thought was required and handed over the detail design to his senior chassis engineer, Terry Mitchell. Terry had already worked on EX179 for Syd, although on that occasion the chassis had already been provided. This was the first time that they had been presented with the chance to start with a clean sheet since the days of EX127 back in the early thirties. It was an opportunity not to be missed. Unveiled to the world in early 1957 it soon acquired the name, ‘roaring raindrop’ and as we have already seen would soon live up to that name as the year progressed.

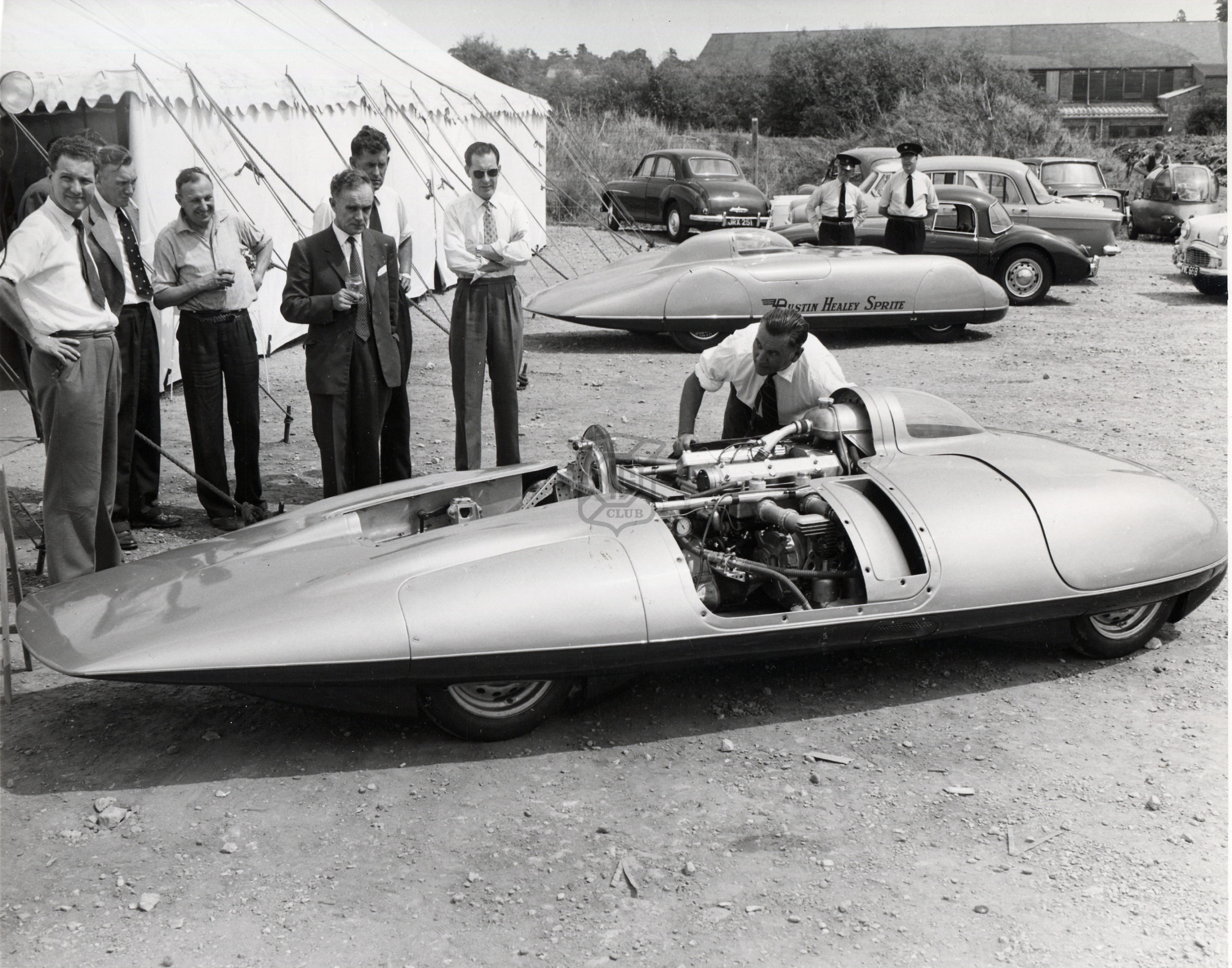

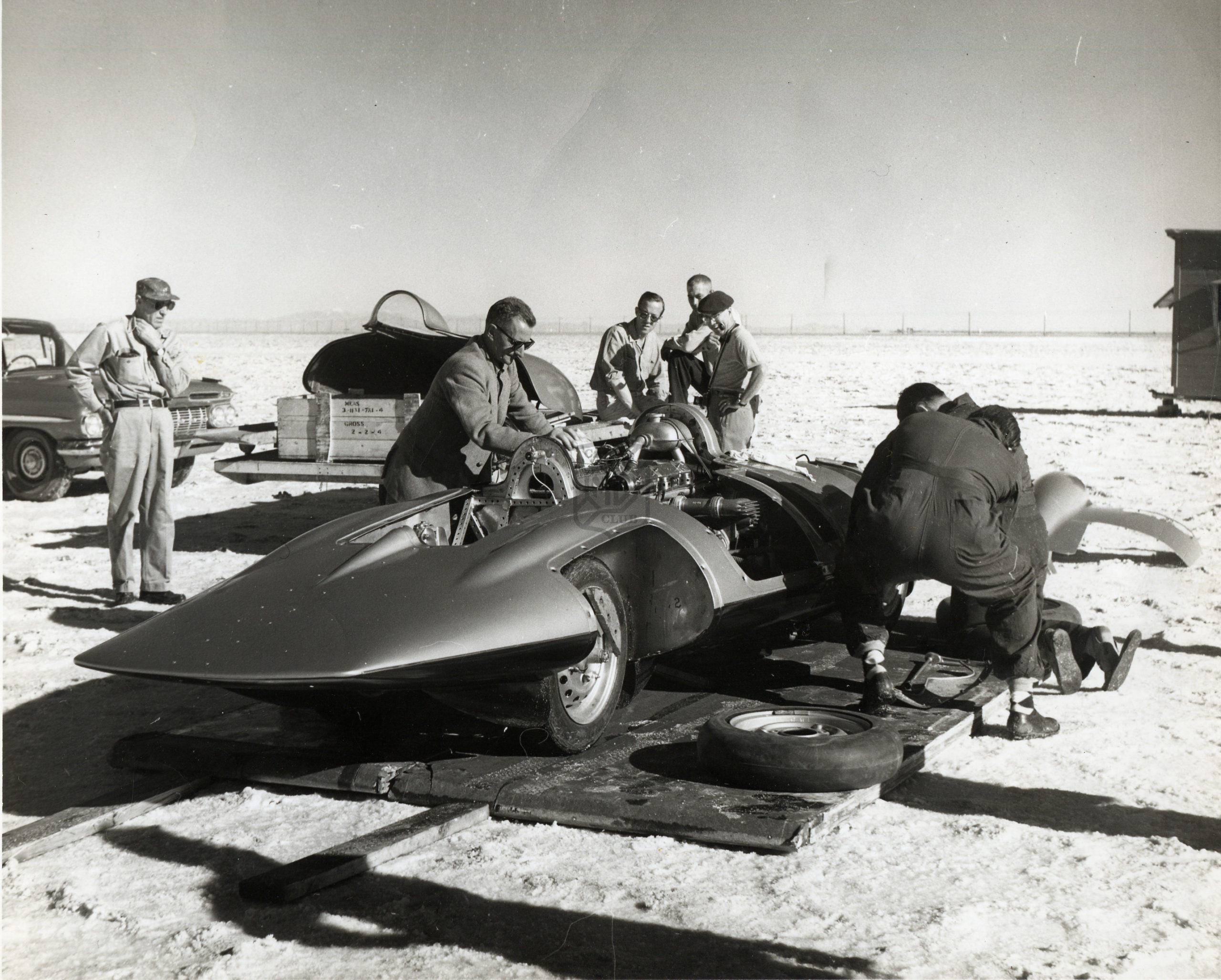

The object of the exercise this time then, was to raise the class F record for the flying kilometre that MG already held, above the 250mph mark and increase the class E records (which stood at much lower speeds) in line with class F. Never ones to miss an opportunity, Abingdon also took along the venerable EX179 (renamed for this occasion as EX219 – Austin Healey Sprite) fitted with an unblown A-series engine to attack long distance records up to 12 hours in class G. For such an ambitious programme it was felt necessary to reserve the salt flats for the whole of September.

A small party was then chosen to accompany the record cars to Utah, led by John Thornley. George Eyston with his assistant Bert Denly would make their own way there at their own expense and make all the necessary arrangements regarding the salt flats. Syd Enever, a man whose record breaking experience was second to none would look after the engineering side of things assisted by development shop foreman Alec Hounslow who had supervised the build of the cars and was responsible for their preparation. Jimmy Cox, Abingdon’s engine development expert, along with his counterpart Brian Rees from Morris Engines Branch, would complete the team.

Cars, crew and drivers (Moss and Hill would arrive later) were duly assembled at Wendover, a small town right on the salt flats, and EX219 was readied on September 8 for its first attempt, at sun up the following morning. The three nominated drivers for this run were Tommy Wisdom, Gus Ehrman and Ed Leavens. Wisdom took the first three-hour stint on the ten mile circle. The salt was in excellent condition and the car was lapping at around 140 mph. Ehrman took the second shift, Leavens the third, with Tommy Wisdom completing the twelve hours. Everything, including the pit stops had gone smoothly, with the car running like clockwork throughout the run.

A brand new set of records had been established and it was now time to prepare the car for the next attempt. The mechanics worked through the night to fit the sprint engine ready for the next day. EX219 was on the salt again by 2.00pm the following day but unfortunately the clutch started slipping on the warm up lap. Attempts were made to cure the problem, but all to no avail. The only solution was to strip the clutch down and replace it. This required another all night session by the mechanics who completed the job by 6.00am the next morning.

Gus Ehrman was selected to drive for this session on the 10 mile circuit. As the result of the previous day’s running the salt had begun to break up in a couple of places and it was agreed that Ehrman would attempt to run wide in order to circumnavigate them. He was lapping at around 150mph when his first attempt at avoiding the rough salt resulting in him spinning out losing 45 seconds. It was decided to keep going but on lap thirteen he lost it again; this time spinning for approximately a mile inside the circle resulting in his disqualification.

This attempt had been made on tyres that had had most of the tread buffed off, to reduce the risk of it becoming detached during the run. A fresh start was therefore made using fully treaded racing tyres. This time there were no problems and the one hour record was established at a speed of 146.95mph. Five other records were recorded from 50 km to 200km along with a whole host of American national records.

It was now time for the team to move to the sprint straight. They were advised that it would take the U.S. Auto Club approximately 24 hours to relocate the timing equipment. The MG team therefore scheduled their first attempt on class F for the following evening (Saturday 12 September). What the team hadn’t bargained for was the rain that came during the night, rendering the salt unusable.

Whilst waiting for it to dry out, it rained again and continued to rain until the following Tuesday, by which time the whole of the salt was covered in half an inch of water. The only thing that the boys could do was to settle down to a long wait until the water had evaporated. By now both Moss and Hill had arrived in the States fresh from the Italian Grand Prix at Monza. John Thornley decided that there was little more that he could usefully achieve so packed his bag and returned to England.

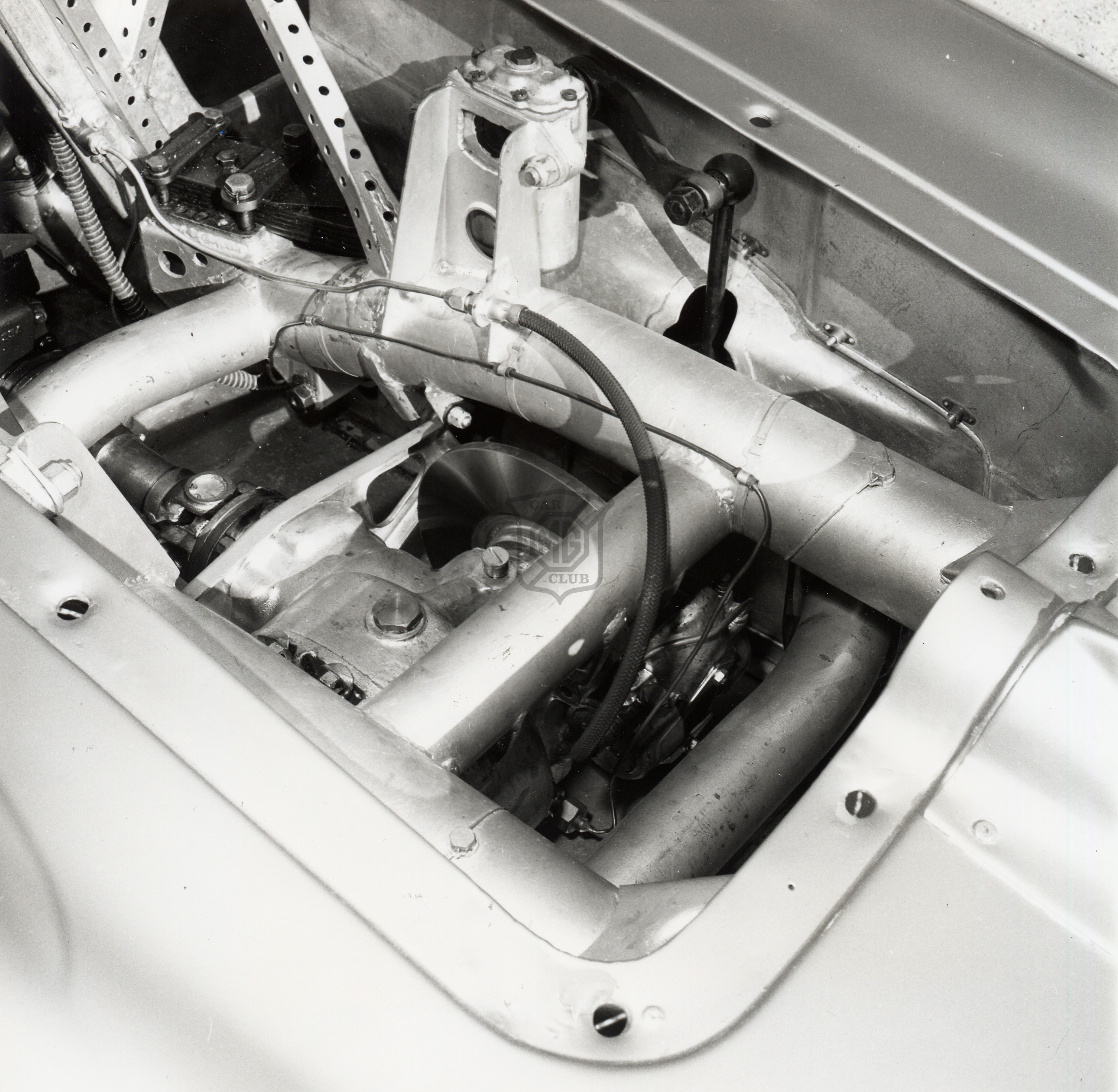

By the Monday of the following week the salt appeared to be drying quite well and it was hoped that it might be possible to commence running again by the end of the week. Because they were losing so much time the decision was taken to rehash the programme. The sprint run planned for EX 219 would be abandoned in order to concentrate on EX 181. Even then the programme would be reduced, by cutting out the class F attempt (MG already held these records anyway) in order to focus on the class E records. This meant installing the blown 1509cc engine in place of the 1489cc class F unit. Apart from being bored out 20 thou oversize, this engine was identical to the smaller capacity unit.

Although MG were confident of beating the existing class E records by a considerable margin, they also wanted to better the class F records set up by Stirling Moss in 1957. The salt had not in fact dried sufficiently by the projected date, and the waiting would continue for at least another week. Thornley had seriously considered the possibility of cutting their losses and abandoning any further attempts. However, after further discussion, and at the express request of George Eyston, he agreed to allow the team to remain for the time being. Stirling Moss needed to return to the U.K. before the end of the month in order to race at Oulton Park, therefore handing over the reins to reserve driver, Phil Hill.

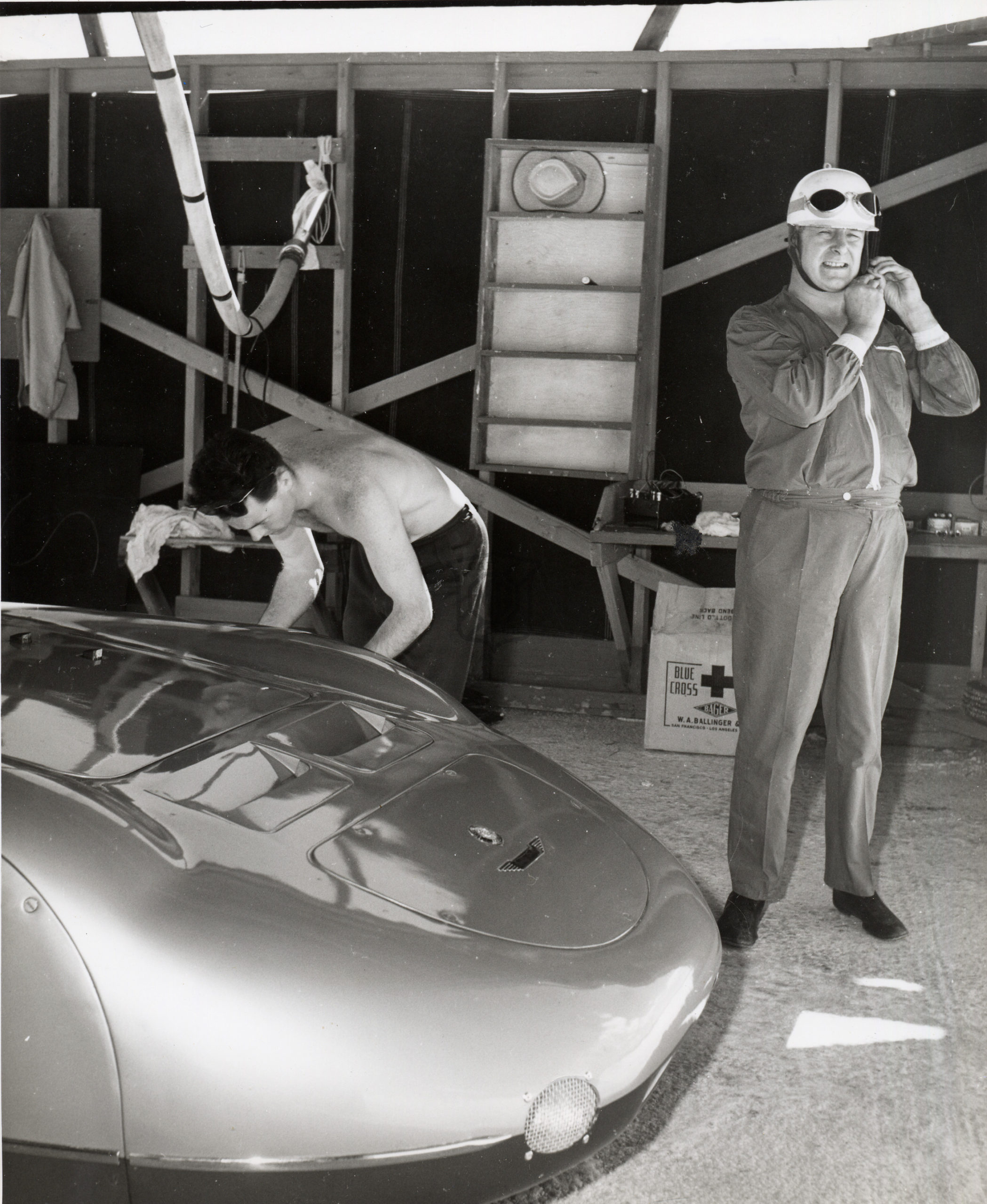

In the event, it was October 3 before it was at last possible to run the car. The salt was far from ideal with the car experiencing considerable wheel spin when initially starting off. Hill made his first run (northwards) at 4.27 in the afternoon, which, it has to be said, was not without a certain amount of drama. Jimmy Cox explained that he and Brian Rees had driven down to the far end of the course in order to turn the car round for its second run.

This had to be effected within the hour for the run to count. Suddenly Hill was upon them and as they opened the canopy he leaped out shouting “the red light’s on, the red light’s on”. Since its last outing in 1957, the car had been fitted with a Graviner, aircraft type, fire protection system and Phil was convinced it was telling him that there was an engine fire! Jimmy continues “we couldn’t see any smoke coming out but when we removed the engine cowl to check that everything was in order, we found that one of the small copper tubes designed to carry the extinguisher fluid around the engine bay had become trapped under the cowling, and as a result had fractured.

This is turn had activated the warning light. Thankfully Phil hadn’t pressed the button to activate the system which would have filled the engine compartment with foam and toxic fumes!” Having done the necessary checks and mopped up some of the excess fuel that had spilled out of the carburettors (a methanol/acetone mix; Hill called it liquid dynamite!), the car was turned around ready for the return run. Assured by Jim that everything was now o.k., Phil climbed back into the cockpit and readied himself for the return leg.

The two men then had to push start the car again. “It wasn’t easy”, explains Jim “I know it’s a light car but we were giving it all we’d got and it just popped and banged. We began to think that it wasn’t going to start and the nearest help was some fourteen miles away with no means of communication! It was still popping and banging when we got to the point where we couldn’t keep up with it. This went on for about another 50 yards and the suddenly the engine burst into life. It was a beautiful sound and you can imagine our relief as we watched Phil disappearing into the distance”. The turn round had in fact taken just over half an hour but to the two men it had seemed an eternity.

Brian and Jim drove back to the start line in Phil’s wheel tracks and once there it soon became apparent from the recorded times that the attempt had been a success. For the team, however, there was still work to do. EX181 had to be unceremoniously loaded onto the back of the truck, driven back to Wendover, hosed down to remove every vestige of salt, then stowed away in the garage for the night. There was just time to eat before a taking short stroll up to the Stateline Hotel for a celebratory drink. The ‘Stateline’, strategically located a few yards over the border into Nevada, was simply the only place for miles around that the boys could purchase a beer, as Utah enjoyed the distinction of being a ‘dry’ State.

The news of Hill’s success had been relayed back to Abingdon by Telex and was received with both relief and delight by John Thornley who couldn’t wait to pass on the good news. Congratulatory telegrams were soon on their way, both to the team in America, the various parts of the Corporation (in particular Engines Branch) that had assisted in the venture, and of course the suppliers without whose unstinting support the whole thing would not have been possible.

Sadly this would be Abingdon’s last excursion to the salt flats, but of course fresh challenges lay ahead for Syd Enever and his team. High on the agenda was the need to develop a new car to replace the aging MGA. I think history has shown that exercise to have been pretty successful too.

MG Car Club

MG Car Club