Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

George Eyston: The King of Speed That Time Forgot

By Jeff Gibson

The illustrious names of Campbell, Cobb and Seagrave will spring to the minds of most people when asked to identify famous British land speed record breakers. Indeed, their place in history is today suitably celebrated by a series of bends at Thruxton, the country’s fastest race circuit. However, there is one name frequently overlooked in these illustrious speed kings, that of Capt. George Eyston.

In addition to his Land Speed Record exploits, Eyston had many associations with the MG marque during a career as a designer, engineer and fearless racer that spanned three decades. For whatever reason, his memory seems to have faded from people’s memories, a great injustice given his record of achievement.

Eyston duelled with Cobb on the baking Bonneville Salt Flats, twice breaking the LSR in 1937/8 at the wheel of a seven-ton, 73 litre, and 4,000 bhp leviathan called Thunderbolt. In MGs, he had already been snatching records from the grasp of Austin, and, after the war he carried on breaking records in the MG EX179 at Bonneville until 1954.

Eyston took Campbell’s 301 mph LSR up to 357 mph, almost six miles per minute; won his class and the team prize in the Mille Miglia for MG in 1933. He was a contemporary of Sir Henry Birken, Earl Howe, and Earl of March, and, of course, his LSR adversaries Campell and Cobb. At this time the average road car could do little more than 50 mph, the huge speeds achieved by Eyston and company brought them fame and glamour. Speed was king and record-breaking was headline news at this time aircraft were only just faster than cars with the Airspeed Record standing at only 440 mph.

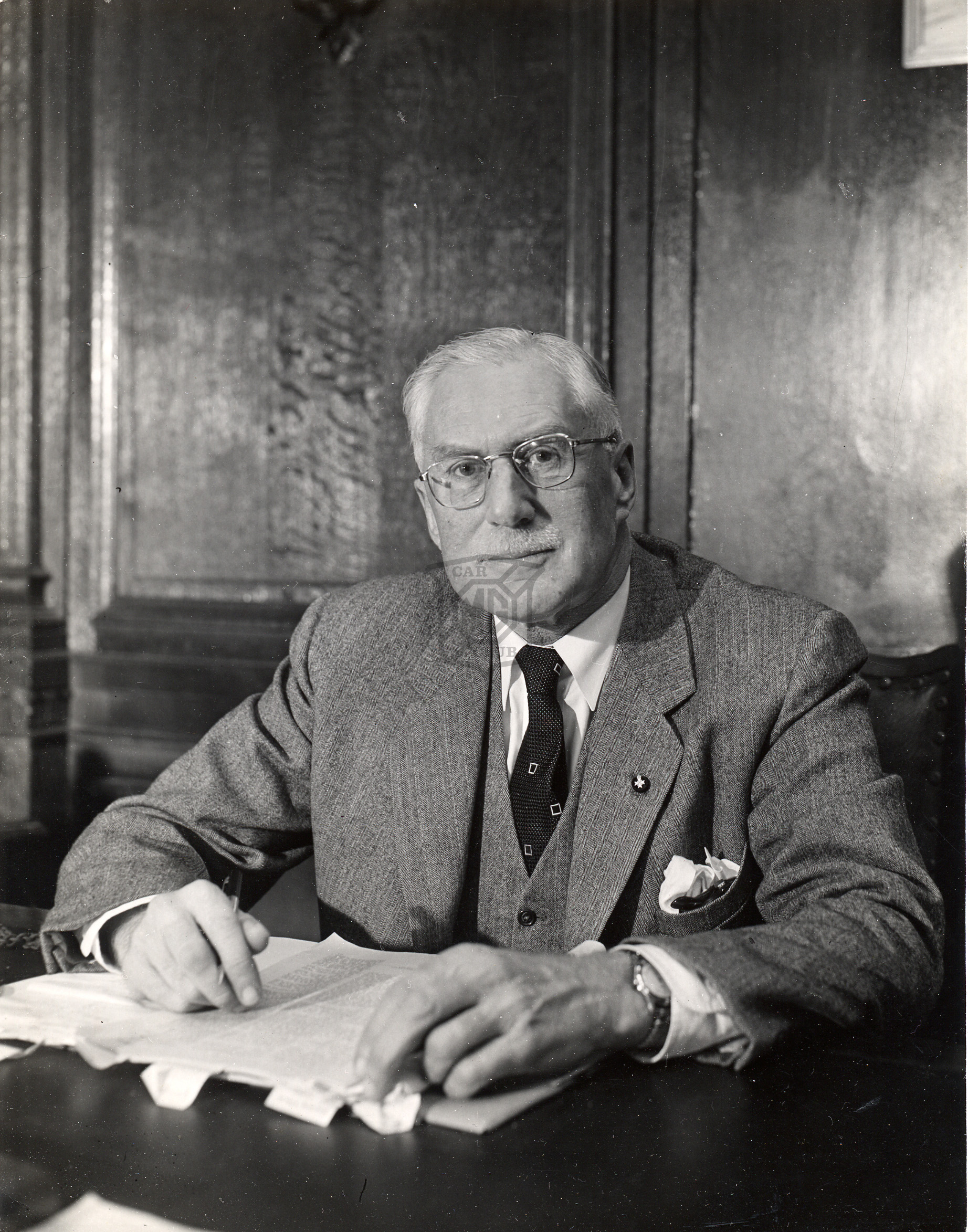

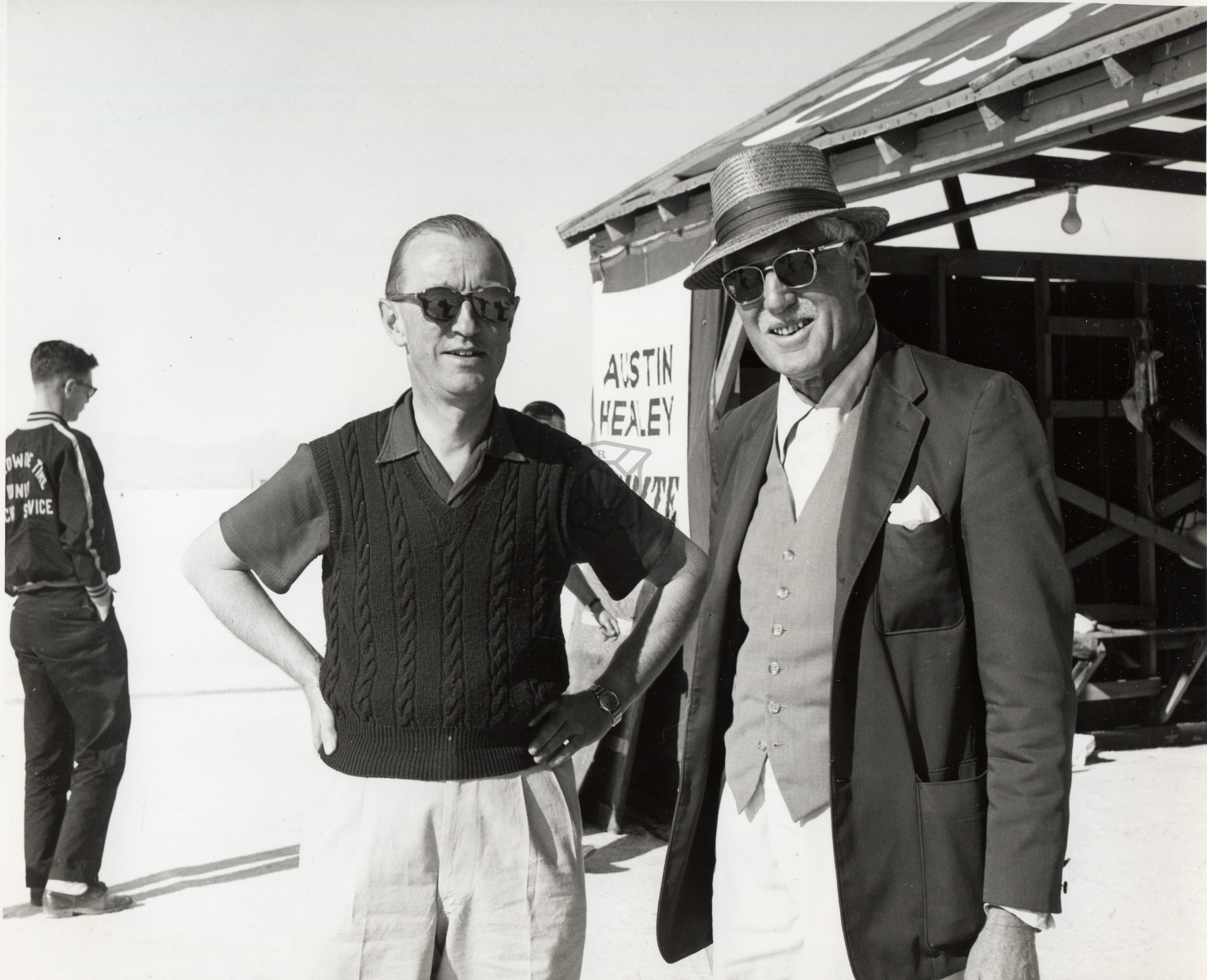

I had the privilege of meeting Eyston several times in his later years before his death in 1979. He was a charming and unassuming man, happy to discuss his exploits. In period, his typically British sense of reserve must have contrasted with some of the larger-than-life characters of his contemporaries. Perhaps this lack of any brash, self-promotion may have ultimately contributed to his fading from the nation’s collective memory.

The Road to Bonneville

George Edward Thomas Eyston (1897-1979) was born into one of the country’s oldest Catholic families who could trace the family back to Sir Thomas More. He qualified in engineering at Trinity College, Cambridge and began his motor racing career in the 1920’s driving a variety of cars, such as Aston Martin, Alfa Romeo, Lea Francis, Stutz and Bugatti, with some success.

He was a Director of Powerplus, producing small lightweight superchargers, and was looking for a suitable small car to break records in the 750cc class. At the time, car manufacturers set great store by claiming international speed records over various distances for a variety of engine sizes, which they used in product marketing and promotional activities.

A meeting with Cecil Kimber at Abingdon resulted in the building of the first purpose-built, record breaking MG, the EX120. Records in 750cc class were predominately held by Austin with their supercharged Seven-based cars. The race was now on between MG and Austin to produce the first 750cc car capable of 100 mph.

With a Powerplus superchager fitted to a much modified M-type engine, Eyston achieved this goal at the wheel of the EX120 in 1931 on the banked Montlhery circuit, reaching 103.13 mph. In a later run, Eyston was hospitalised after the car caught fire.

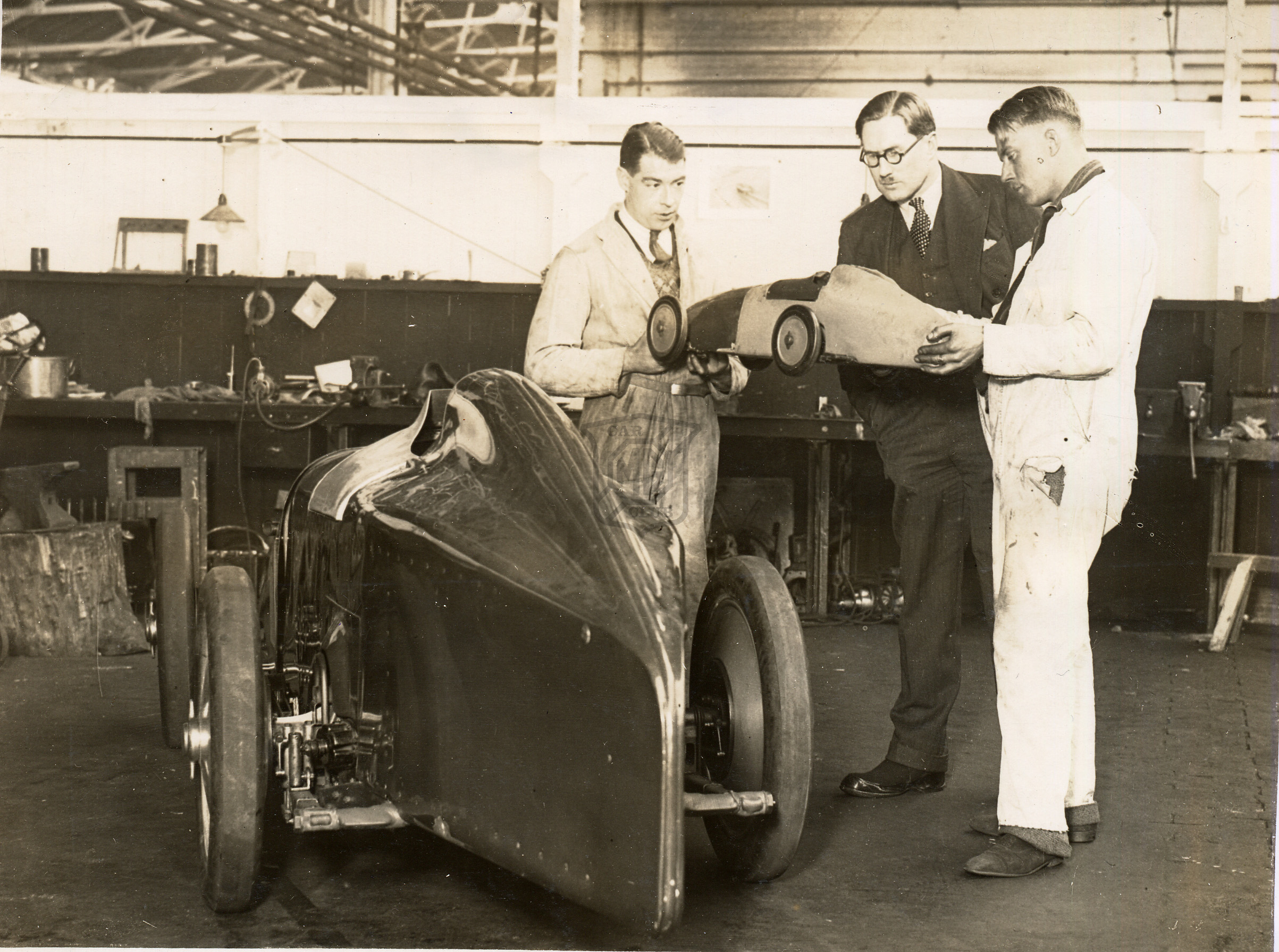

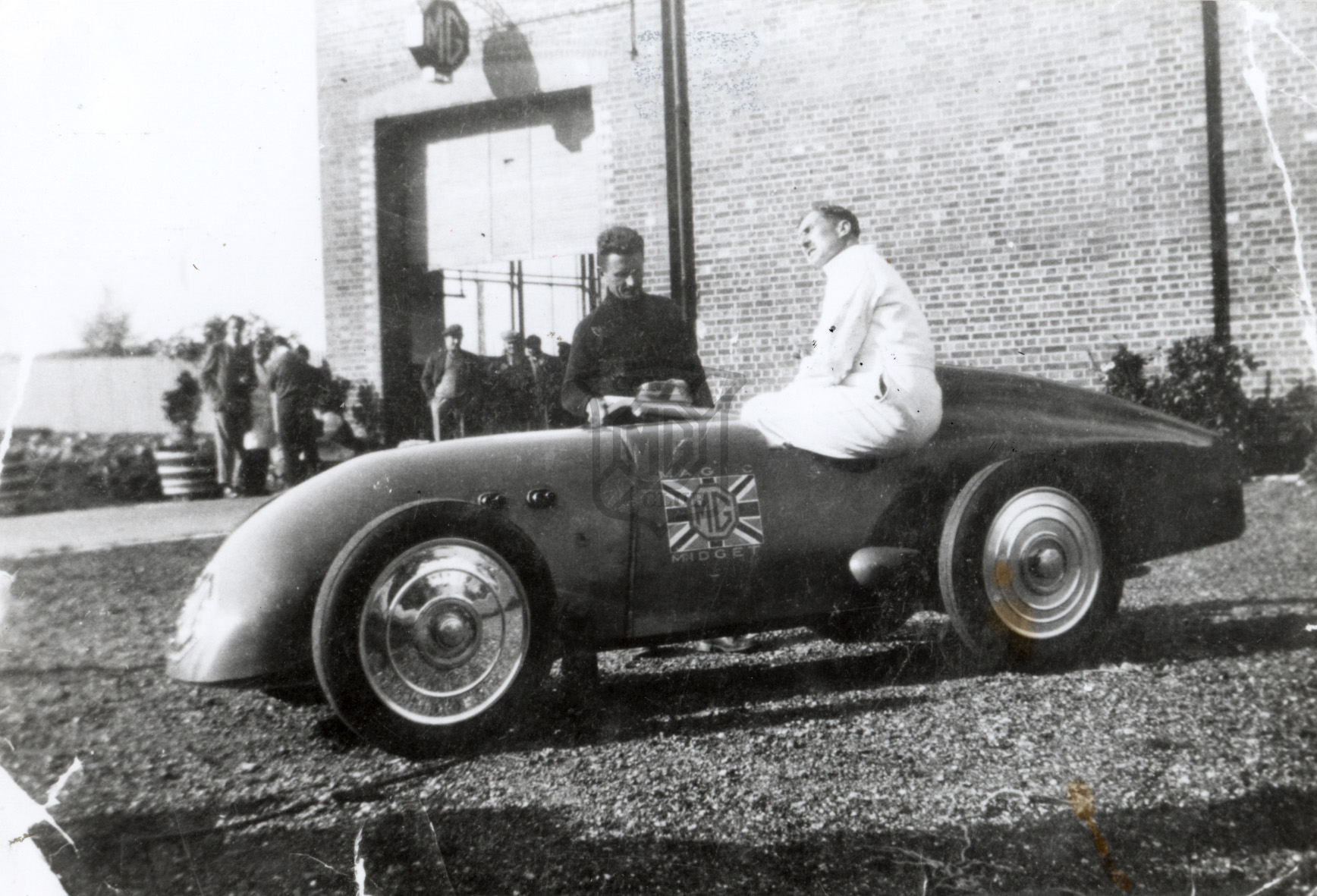

Undeterred, MG and Eyston did not rest on their laurels. Almost immediately, the more sophisticated EX127, the Magic Midget, was built. A quarter scale model was tested in the Vickers wind tunnel at Brooklands which resulted in the shaping of a much more aerodynamic body (see photo). EX 127 also had an offset driveline, allowing the driver to sit much lower in the cockpit.

After an unsuccessful record attempt on Pendine Sands, near Tenby in Wales, Eyston achieved 120 mph in EX127 back at Montlhery in 1932. In many of his long distance record attempts his personal mechanic, Bert Denly, acted as co-driver. The difference in height between the two was considerable, probably eight or nine inches, and must have posed real problems when they were sharing driving duties in the same car. The Magic Midget was altered the following year to improve the aerodynamics, but Eyston was now unable to fit in the car so Denly took over the driving and pushed the 750cc record up to 128.63 mph.

Shortly after the launch of the K3 Magnette in1933, MG entered a team of three cars in the 1933 Mille Miglia. Sir Henry Birkin’s Magnette set the pace and soon disposed of the Maseratis, MG’s main competition in the 1100cc class. However, Birkin’s car dropped a valve and the Eyston/Count Lurani entry took over the class lead, smashing the 1100cc record. With the remaining Magnette, the remaining two cars finished first & second in the class also taking the team prize for MG.

Eyston had further MG record breaking success in 1934 moving up to the 1100 cc class with a special K3 Magic Magnette Ex135. Painted in contrasting horizontal stripes this car was nicknamed the “Humbug”. With this car he broke no less than twelve 1100cc class records at Montlhery.

At this time, Eyston was breaking speed records in variety of cars over both short and long distances, including a Chrysler chassis powered by an AEC diesel engine from a London bus!

Rewriting the record books

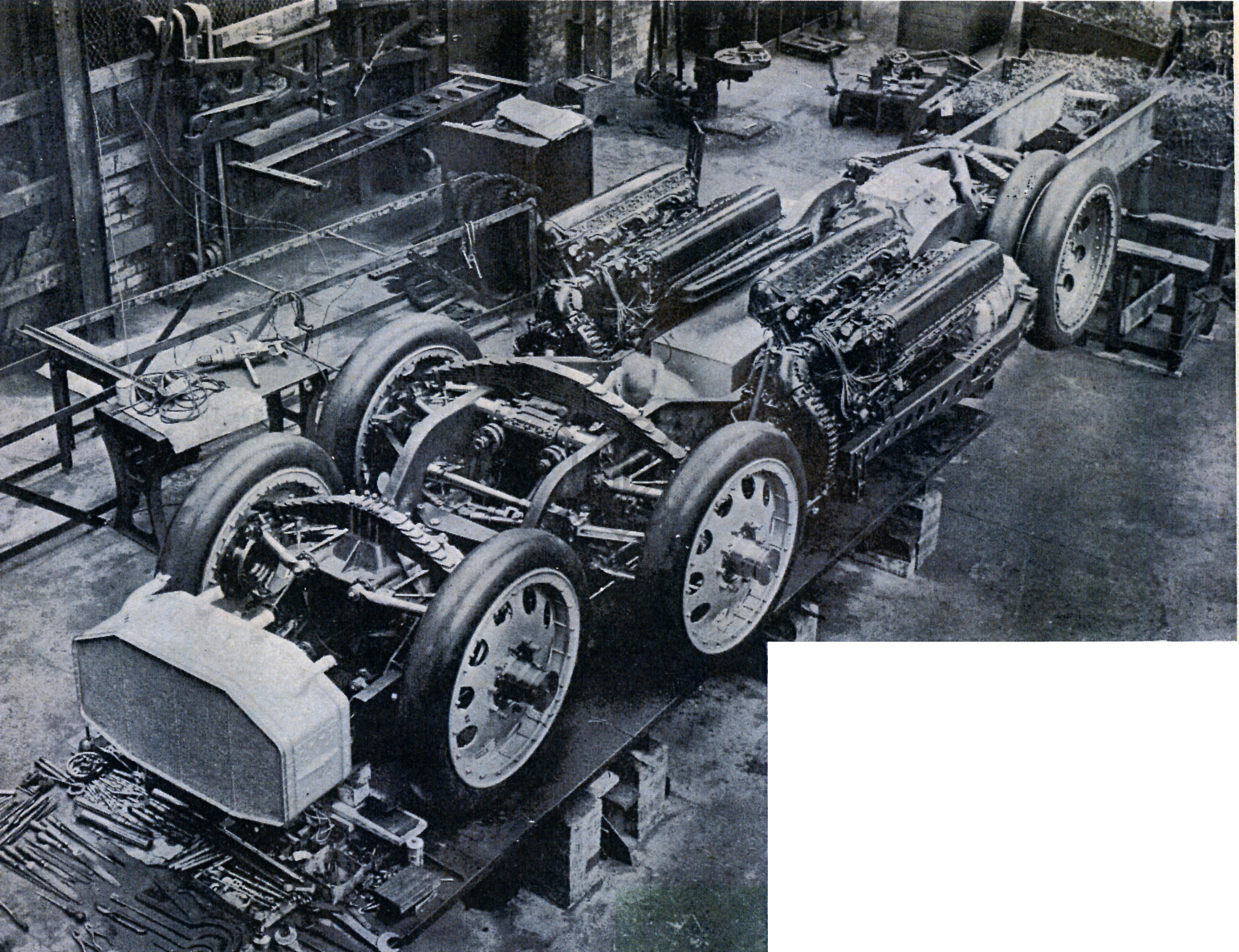

Thunderbolt’s body and chassis was constructed by Bean Industries of Dudley, which was later to become part British Leyland and continued to supply castings to MG Rover Group until their demise in 2005.

The two front axles steered the car and were independently sprung by leaf springs, an innovative design for the time. The single driven rear axle had twin rear wheels on each side to give traction on the salt flats. Initial braking was achieved by air brakes, large opening flaps in the side of car which slowed it to about 180 mph, when the mechanical brakes could then be engaged. The mechanical brakes were a type of disc brake although there action was similar to a clutch.

Eyston returned to Bonneville in 1938 with a modified car. To improve its aerodynamics, the octagonal intake was now closed up – ice was used for engine cooling – and the previously open cockpit was also enclosed. With these improvements, Thunderbolt once again broke the LSR at a speed of 345.50 mph.

Eyston’s ambition was now focused on the ultimate challenge, breaking the world speed record. To do that, he would have to develop a vehicle with huge power. The result was his awesome Thunderbolt, a huge six-wheeled car weighing seven tons and powered by two 36.5 litre Rolls Royce R-type V12 aero engines, mounted amidships, producing in excess of 4000 bhp.

However, competition on the salt flats arrived in the shape of John Cobb’s Napier Railton. Cobb was already the outright lap record holder at Brooklands and Reid Railton had designed a much smaller and lighter LSR contender than Eyston’s Thunderbolt. Cobb soon had his car out on the salt and moved the LSR up to 353.30 mph. The duel was on.

The first objective was to break Sir Malcolm Campbell’s LSR of 301.34 mph and in 1937 Thunderbolt successfully achieved 312.00 mph on the Bonneville Salt Flats. Interestingly, although Thunderbolt had no connections with MG, the car’s front air intake was octagonal in shape.

Eyston immediately carried out further modifications to Thunderbolt. In the quest for improve the aerodynamics; he removed the car’s vertical rear tailplane, even though this risked reducing high-speed stability. The flanks of the car were also painted black as initially the new photo electric timing equipment had failed to pick out the polished aluminium bodywork against the brilliant white salt.

In WW II Eyston was involved with the Allied Landing and awarded an OBE. After the war he continued to participate in record breaking. He supervised MG’s Bonneville record attempts and was still driving the TF-engined, EX 179 as late as1954, when he was 57 years-old. He then managed the MG EX 181 record attempts of Phil Hill and Stirling Moss in the late 1950’s.

Cobb held the record for less than 24 hours, the modified Thunderbolt was out on the salt again and now moved the record up to 357.50 mph, slightly under six miles a minute. This was, however, to be Eyston’s final LSR attempt. Later, Thunderbolt was tragically destroyed by fire while on show in New Zealand. As a postscript, one of its Rolls Royce R type engines survives and is now on display at the Science Museum Aeronautical Department.

During conversations with Eyston, I once asked him to describe what it was like driving Thunderbolt in excess of 350 mph. He said it was like driving on the edge of six knives! The huge centrifugal force on the tyres would push the centre of the tread so far from the wheel that the contact point with the ground resembled no more than a knife-edge. Typically, he made little of it, but the bravery required to drive a huge car at such speed with so little grip is hard to comprehend.

Balancing on a knife-edge

He seemed to be more proud of his achievements with the Magnette in the 1933 Mille Miglia. He had a British Racing Green Jaguar XK140 Coupe (Reg Number XPJ 1) and on the walnut dashboard was the large Mille Miglia badge presented to all finishers. The badge was in the shape of a wooden steering wheel, enclosing a map of the Mille Miglia route, with the names of George Eyston and Count Lurani engraved on it.

At the time the specification for an XK140 would be wire wheels and open rear wheel arches however Eyston’s had the unusual specification of steel wheels and the spats enclosing the rear wheel-arches to improve the aerodynamics based on his record-breaking exploits. Apart from his driving achievements Eyston was a keen shot and fisherman.

During conversations with Eyston, I once asked him to describe what it was like driving Thunderbolt in excess of 350 mph. He said it was like driving on the edge of six knives! The huge centrifugal force on the tyres would push the centre of the tread so far from the wheel that the contact point with the ground resembled no more than a knife-edge. Typically, he made little of it, but the bravery required to drive a huge car at such speed with so little grip is hard to comprehend.

Post War George Eyston was a Director of Thorneycroft and C.C. Wakefield makers of Castrol Oil. Bert Denly his pre war mechanic and record breaking co-driver worked in Castrol’s engine test department in the 1950’s and 60’s. I did some work experience here in my school holidays and was fascinated by the advanced R Type MG and asked Denly what is was like to drive. Unfortunately, I was disappointed by his comments, which were not flattering.

Of course, Eyston never once expressed any disquiet over an apparent lack of public recognition for his achievements. Always unassuming and self-effacing, his complete lack of ego was refreshing to behold. His place in the history of MG and the LSR is undoubtedly assured, even if he is not always given the credit he deserves.

See Captain George Eyston in action

Visit www.britishpathe.com and enter George Eyston in “search the archive”.

You will find film of Ex120 at Brooklands, Pendine and Monthlery. Together with Thunderbolt, Speed of the Wind right through to EX 181 in 1959

MG Car Club

MG Car Club